Aim high (part I)

The (re) emerging conversation over cloud seeding and geoengineering

Hello friends, it’s been awhile. I’ve been away from this platform for a couple of months - to be frank I was searching for a new topic to write about, and nothing really landed with me until a couple of weeks ago. I did however, had a great discussion with the awesome Lorraine Schneider about managing complex risks and why climate security matters over at her newsletter, Futurisk. And Seb Tranaeus and I hosted the first of our “Resilience Rendezvous” adaptation drinks last month. We’re looking forward to hosting the next session after everyone returns from their summer holidays, so stay tuned to here and my LinkedIn for more details.

In this edition, we’ll look at the opportunities and risks of playing around with the weather. It ain’t all bad as some doomsayers would have it, but neither is it the proverbial sunny uplands.

Let’s go.

Is lunch free today?

What if there was a low cost, high impact solution to many of the woes afflicting our planet and the suffering of billions? And what if I told you that solution is possible today? And what really smart people you trust told you that this means you can redirect all that money you were going to spend on renewables and net zero toward something else - school vouchers, transport infrastructure upgrades, F-35s, Mpox vaccine research, Storm Shadow, etc? If you were a leader worried about your country’s long term prosperity in a volatile environment, pulled by competing priorities, this type of silver bullet sounds grand.

Enter geo-engineering and its distant cousin cloud seeding. Let’s start with the latter and work backwards so we understand why this may become very appealing to the leaders, innovators and investors of the near future.

Cloud seeding 101

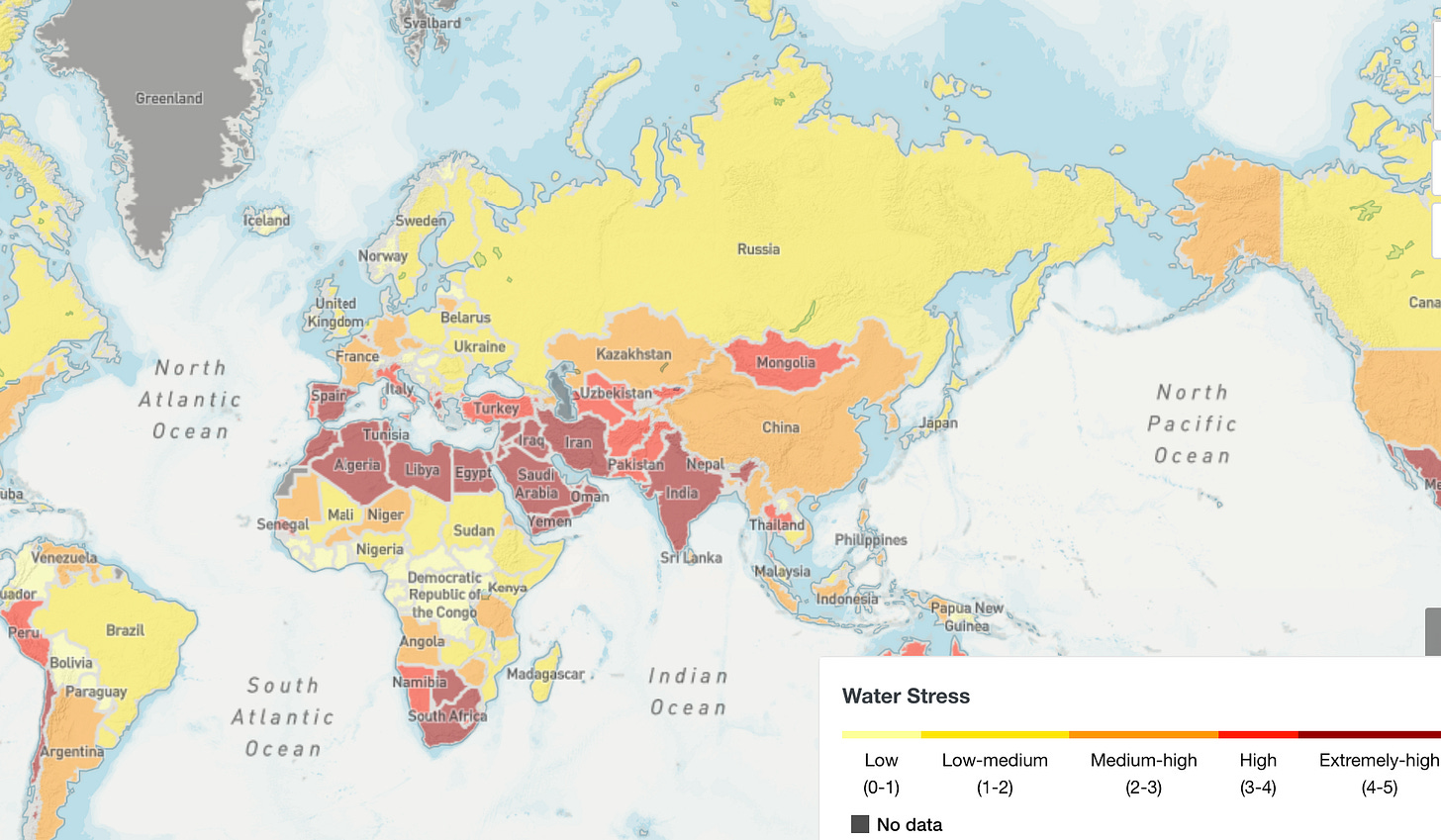

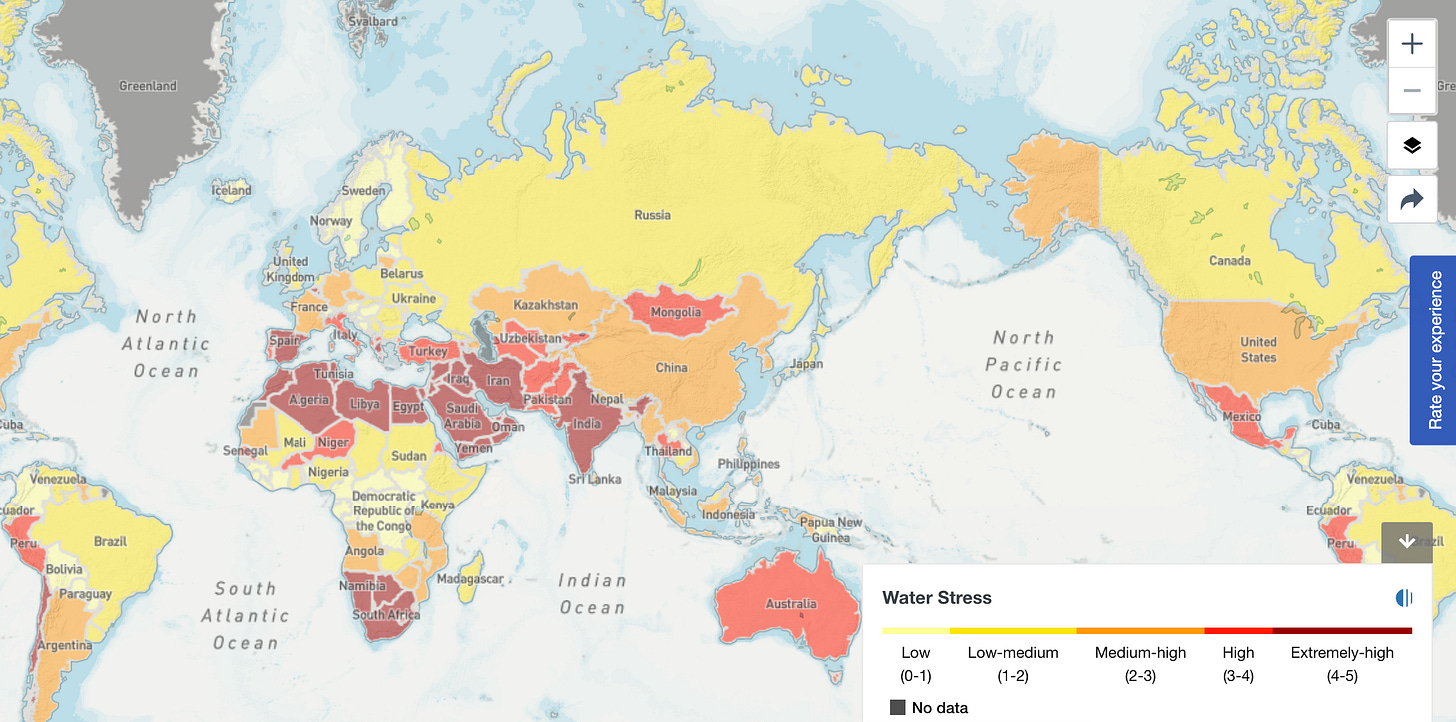

As I’ve discussed in multiple earlier editions, water matters - for life, sustenance and economy. For countries and regions where water scarcity is a fact of life, cloud seeding presents an opportunity to “smooth out” the peaks and valleys of water availability throughout the year. The technology and methodology is quite mature: it’s been around since the 1940s and something actively pursued by the US government for military applications through the 1970s. Today, over two dozen countries are known to employ cloud seeding at varying levels of sophistication and intensity, including US states and the UK, with China at the forefront.

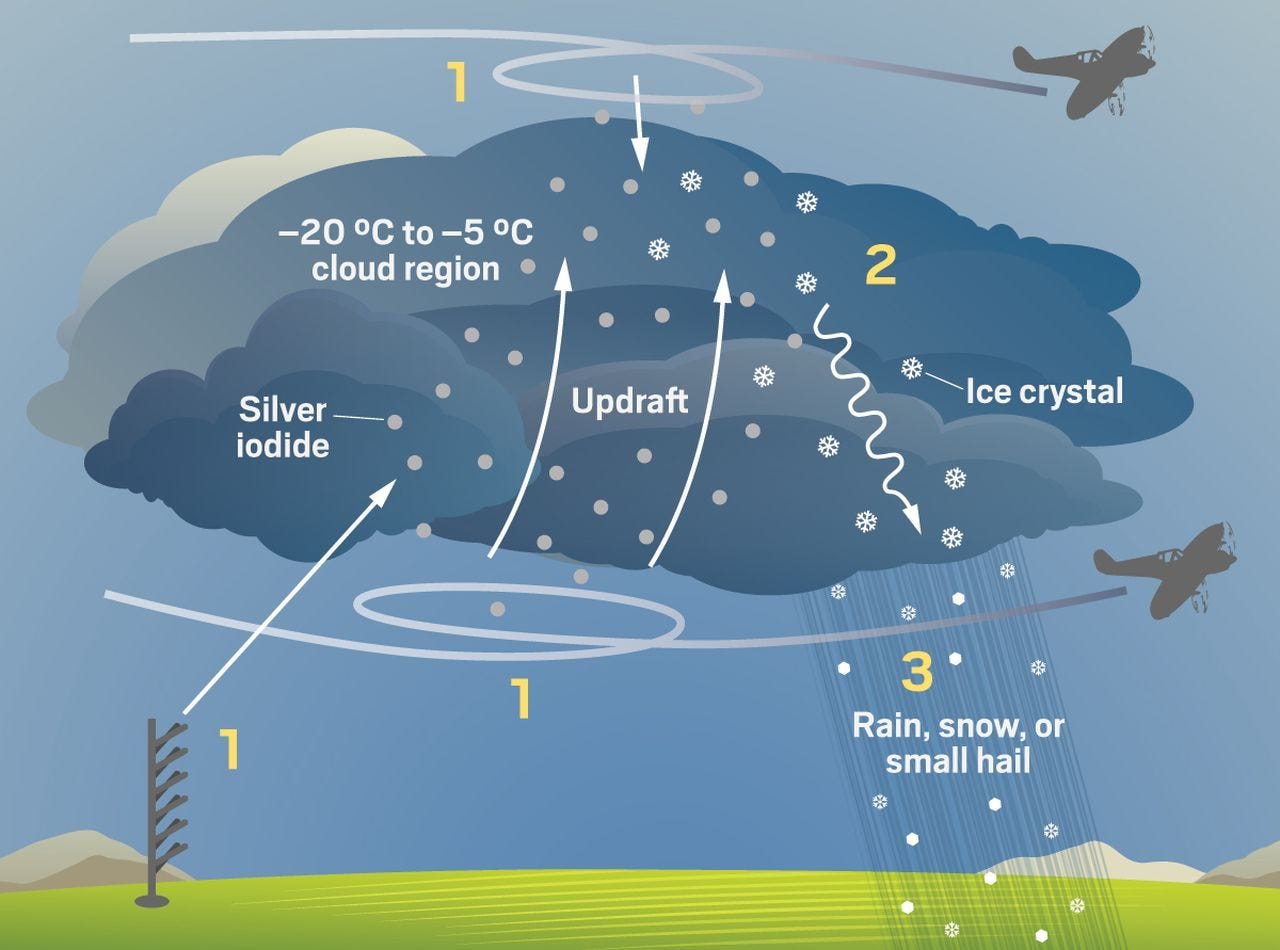

Cloud seeding is done through taking advantage of cloud formation and condensation phenomena which rely on moisture build around air particulates. This process occurs naturally, but cloud seeding artificially pumps additional volumes of particles (normally silver iodide but other compounds have been used) into cloud cover from planes or ground based launchers. Silver iodide serves as artificial nuclei for moisture condensation, leading to greater precipitation. Typically, this is for the benefit of water reservoirs and agricultural use and local community water supply - often by building up snowpack or improving streamflow.

So far, so good. Responsible actors (such as those working with the Desert Research Institute in the western US) set clear use case and safety guidelines to maximise the accuracy of impact - efforts must target already-formed clouds to induce rain/snowfall. Satellite imagery, ground / air based-radar, microwave radiometers and visual observations are commonly employed to target the right clouds with supercooled water already present at the right time for maximum impact. Care is also taken to not overuse silver iodide over a specific area, as well as avoiding negative impacts during busy travel times or rainy season. Studies since the 1970s have shown that, across different regions ranging from Australia to the US that cloud seeding tends to increase snowpack or rainfall by 5-15%. So while not a massive game-changer, it can smooth out deeper troughs in water levels on a perennial basis.

For local governments where water is a lifeline, cloud seeding is essential to water resource management, within and across jurisdictions. In 2023, the Santa Ana watershed authority in southern California approved a four-year, $1.2m programme for cloud seeding across multiple counties. Why did they do it? Because if successful it would save them money from buying (pricey) water from the Owens Valley and beyond.

In arid locales like Jordan and the UAE, this technology is deployed to benefit local agriculture to sustain national food security and the livelihoods of farmers. Russia and Thailand have used it to suppress heatwaves and wildfires. Private firms have deployed it to reduce damage from hail in order to reduce insurance costs through cloud seeding’s impact on the composition of rain clouds. In China, where food security is ideologically engrained into how it conceives national security and state legitimacy, cloud seeding benefits agriculture, water flows between regions, improve drinking water quality and on occasion for political objectives (clearing the skies ahead of the 2008 and 2022 Beijing Olympics). The US is estimated to spend $10-$15 million annually, while China spends over $80m.

OK well what’s the problem - no it is opportunity

Is there a moral hazard here? I would argue it depends on who holds the wand on deploying the technology. Where government actors clearly define the use and target objectives, effective consultation with citizens and businesses would reduce negative perceptions and impacts of the deployment e.g. one farmer benefits at the expense of another. It also helps that clouds must form on their own accord before cloud seeding can be considered, lowering social risks arising from “picking winners.” This is one area where solutions which deploy AI-informed weather models, IoT and drones to more precisely target cloud formations and estimate precipitation can benefit all key actors for the sake of the allocation and sustainability of limited water resources within a specific geography. Where done properly and responsibly, cloud seeding is an additional adaptation measure which governments deploy to ensure the resilience of their water and food supply, as well as their people’s livelihoods in the face of worsening physical risks from climate change. Paired with weather intelligence platforms, sensor and telemetry data, alongside water infrastructure investment / O&M adjacent to water-tech solutions which reduce loss (AI-enabled crack detection in concrete or pipes, for instance), cloud seeding can be effective where marginal gains in rainfall or snowpack is crucial to achieve local economic and social outcomes.

But can this go wrong, somehow?

Should the technology’s deployment become more decentralised / democratised, the perception of misuse and winner-take-all of water may arise, creating potential conflicts within and between communities. Effective and transparent governance over how the technology is used relative to water management would be critical to reducing these potential harms. Unfortunately, such governance is often lacking in jurisdictions where the technology can be most beneficial - particularly in transboundary watersheds where riparian rights are contested or poorly enforced. In the Western US, cloud seeding is implemented at the water authority level, sometimes with federal funding. These basins are often under long-term water stress, creating high-profile disputes over water allocations. In this context, cloud seeding is attractive - policymakers find it easier to “add” supply than discussing who and how much to cut back.

At the state level, there is a limited, but acknowledged concern of the political implications of the technology. The US military backed away from this space after Operation Popeye during the Vietnam War because it led to worsened flooding during monsoon season (more on this later). To date, cloud seeding has not been pursued by any country on a systematic scale, and there is no evidence that it has led to shifts in weather patterns.

But I leave open the possibility of what happens if the technology is scaled over an extended period, partly because it is inexpensive and easily available. Rather than reducing water security risks, it redistributes it if done at scale without adhering to responsible and safe use. Reprising this opportunity in the near-term environment, deploying the technology aggressively in transboundary watersheds like the Indus, Euphrates, Dnipro or Mekong could may be seen as a weaponisation of weather processes, particularly if deployment is poorly timed or executed, or if it exacerbates underlying political and security tensions amongst the entities which the cloud seeding operation would impact. Although patterns are observable by all, attribution of a malicious or harmful outcome where cloud seeding is suspected may not be straightforward; an accuser would need clear intelligence that delivery mechanisms (range of rockets, drones, balloons, planes) were deployed with such intent, and that overall levels or intensity of precipitation / flooding was somehow unanticipated. Conversely, cloud seeding could be one area of interstate cooperation, building confidence between jurisdictions over shared resources and benefits.

As water stress and scarcity is projected to worsen significantly in the temperate regions by 2040, with greater swings between wet and dry seasons, more countries and private actors are likely to revisit cloud seeding as an additional, convenient tool in the bag as short-term band-aids to prop up water supplies, agricultural production and avoid urban water crises.

Greater public and media attention toward cloud seeding could see the injection of winner-take-all rhetoric and disinformation around the technology: a very quick search on X shows a range of posts, some likely from inauthentic accounts, expressing concerns about the environmental risks of cloud seeding, conflation with geoengineering, alleged removal of vitamin D and poisoning of groundwater. The history of the technology, use by the state, poor public awareness and knowledge of the science, and perceived adjacency to geo-engineering leaves the greater use of cloud seeding vulnerable to being targeted by disinformation campaigns.

In the next part of this edition, we’ll tack over to geo-engineering, or solar radiation management more formally, and the moral and geopolitical hazards over that technology.

Thanks to Alex Laplaza from Makerain for his perspectives on cloud seeding and climate-tech’s push into the space.

What caught my eye

I’ll be joining a virtual workshop next month, hosted by Loughborough University and the Manipal Academy of Higher Education, to learn more about some of the latest research investigating how climate change and the energy transition are impacting diplomacy, geopolitics and defence. Details in the link - hope to see some of you there.

The recent incidents of sabotage and hosting targeting of corporate CEOs in Europe re-raises the spectre of what private companies should do to protect themselves from state-sponsored actors. This is the stuff of Cold War lore, but nope it’s 2024. Whether it is executive protection, a strong government relations game, insider threat or counterintelligence capability, companies need to understand their external risk profile - and who works for them - to refresh whether they could become, quite literally, a victim of hostile states.

The Global Adaptation and Resilience Investment (GARI) Working Group is hiring for a programme manager.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute is looking for a climate security analyst in its Climate and Security Policy Centre.

I’ll be back soon with Part II: geoengineering redux. Over and out. Until then: