Just how vulnerable are our first responders?

Lorraine Schneider, COO of The Resiliency Initiative talks California wildfires, challenges to emergency services in the US and globally, and how they can stay resilient amid multiple crises

Hello again! I’m deliberately tuning out the sounds of the world for the next couple of months as more important life events are afoot, but I can’t but help to opine just a bit. The twists and turns of global news over the past month is a good reminder to us risk and intelligence professionals that a) not everything out there should be framed and analysed with what “we think” is rational; b) not everyone has a plan; c) people change their minds all the time; d) history is long and short depending on who is asking; and e) the Dunning-Kruger effect, despite its flaws, should be in the mix when we consider where things may head.

OK, onto climate security!

The California wildfires, radical shifts in US government policy on climate, the federal workforce and funding for agencies crucial to primary data collection places emergency management uncomfortably into the spotlight. They’re an essential part of the backbone to our society’s resilience. But are they resilient themselves? And if not, what does that mean and what needs to be done at the local and global scales to ensure this integral piece to climate adaptation and security risk mitigation continues to thrive as part of the solution mix.

To discuss these issues and more, this month I’m joined by Lorraine Schneider, the Chief Operating Officer at The Resiliency Initiative, a US-based crisis management and business continuity consultancy empowering organisations to plan better and recover quicker. Lorraine is a Certified Emergency Manager and has developed groundbreaking training, exercise and preparedness programs serving The Walt Disney Company and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). She holds a Master of Science in International Strategy and Diplomacy from the London School of Economics and Political Science, a Certificate degree in Emergency Management & Homeland Security from UCLA Extension and a Bachelor of Arts in North American Studies from the Freie Universität in Berlin. She is also a former resident of the Palisades and a longtime friend of Securing our Climate.

Hi Lorraine! The wildfires in California were an unfriendly welcome to the year, to say the least. Why do you think the physical side of the fires happened the way they did? We hear everything from poor vegetation management to zoning to DEI.

Having grown up in France and Germany, I’ve always been struck by how differently homes are built in the US compared with Europe. In Europe, houses are typically made of brick, stone, or concrete, whereas American homes are largely wood-framed. While that makes them more earthquake-resistant than brick structures, it also makes them far more vulnerable to fire.

But honestly, that’s just one piece of the puzzle. The real game-changer in the Palisades Fire was the hurricane-force Santa Ana winds, which topped 100 mph and hit during an extremely dry spell. These winds don’t just fuel wildfires—they turn them into unstoppable infernos. In the early hours of the fire, planes and helicopters carrying water and fire retardant had to be grounded because the winds were too strong. A key part of the early response was essentially taken off the board. Meanwhile, the fire kept spreading fast.

Another factor is vegetation management or lack thereof. With how quickly the climate is shifting, it’s becoming ever harder for authorities to keep up. Southern California can experience multi-year droughts followed by periods of heavy rain. Last winter was particularly wet, meaning lots of new plant growth. But by spring, as the dry season set in, all that fresh vegetation turned into fuel, making it a perfect recipe for disaster.

And then there’s the wildland-urban interface—the areas where homes and businesses sit right up against undeveloped land. California has a lot of that, and it’s a double-edged sword. It’s what makes the coastline and mountains some of the most iconic places to live, but it also makes them some of the most dangerous. Sadly, I don’t think the threat of future fires or rising sea levels will stop people from rebuilding in these high-risk areas. It hasn’t to date.

The emergency services were stretched to the limit amid online contentions the fire department budget in LA County was cut several months prior- what are the real facts here?

The political fallout from the LA Fires is shaping up to be a textbook case in leadership and crisis communications—or, depending on how you see it, a case study of what not to do. The short version: on February 21, 2025, LA Mayor Karen Bass fired Fire Chief Kristin Crowley, citing a lack of preparedness and the early release of 1,000 firefighters as key reasons. Chief Crowley pushed back, saying the department was already stretched thin due to years of budget cuts and denying claims that she refused to participate in post-incident reporting. She appealed the decision, but the City Council shut it down with a 13-2 vote, making her removal final.

I wasn’t directly involved in these events, so I won’t pretend to have the full picture—but here’s what I do know. From the start of the fires, Mayor Bass faced heavy criticism for leaving LA to attend a presidential inauguration in Ghana despite widespread warnings about extreme fire conditions. To many, her firing of Chief Crowley looked like scapegoating. The reality is that the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD) was under-resourced long before these fires broke out. Back in December, a group of veteran firefighters pleaded with city leaders for more funding, pointing out that dozens of fire engines were out of commission simply because there weren’t enough mechanics to repair them. A recent CNN analysis found that the LAFD is one of the most understaffed fire departments among major U.S. cities, struggling to keep up with both day-to-day emergencies and large-scale events like wildfires.

But this isn’t just about one bad budget decision. It’s about decades of failing to invest in public safety. Equity on Fire, which called for the reinstatement of Chief Crowley, pointed out that the LAFD operates with 62 fewer fire stations than it actually needs to serve a city of LA’s size. Meanwhile, as the population jumped from 2.4 million in 1960 to 3.8 million in 2020, and 911 emergency calls skyrocketed from around 101,000 in 1969 to over 500,000 in 2023, the number of fire stations actually fell from 112 to 106. Chief Crowley warned in December that ongoing budget cuts had “severely limited” the department’s ability to respond to large-scale emergencies—including wildfires. In 1990, LAFD had just over 3,000 firefighters. Fast forward to today: despite massive population growth, that number has only increased by 300.

Now take this same issue and apply it to other critical services—like the Department of Water and Power, which is also struggling to maintain aging infrastructure—and you’ve got a real resiliency problem.

This story isn’t over, and it carries a warning for every city facing wildfire risks, or any other disaster, for that matter. An LA city councilwoman has called for an independent investigation into who knew what and when, and there’s already a push to recall Mayor Bass. But this isn’t just about one mayor or one city council—it’s about every elected official who has a responsibility to protect their communities. When politicians fail, whether through negligence, mismanagement, or simply kicking the can down the road, there should be consequences. Because without accountability, we’re doomed to repeat the same mistakes over and over again.

Do private firefighting services play a positive role? Would we see more people / companies taking this up in the future if they feel the public response they lean on for their crisis management planning may not meet expectations?

Over the years, I've heard a lot of criticism regarding private firefighting services, mainly concerning their role in highlighting inequity in disaster response. Wealthier individuals can afford to hire private firms to protect their properties, which can divert resources away from those who are less fortunate. City, county, and state firefighters view private firefighters as civilians who must follow official orders, including evacuation instructions. In worst-case scenarios, these private services might compete for resources or require rescue themselves, which can detract from the efforts of public firefighters.

On the other hand, it is understandable that some residents and businesses feel compelled to rely on private firefighting services for property protection. With insurance rates reaching record highs and some companies exiting the state entirely, many are motivated to take any necessary measures to prevent their properties from burning.

Ideally, fire agencies would have adequate budgets to meet their community’s staffing, resource, and mitigation needs. Unfortunately, the LAFD is not the only one experiencing budget cuts while the threat of more devastating fires increases. In emergency management, we often emphasise the significant benefits of public-private partnerships. Perhaps it would be worthwhile to explore cross-sector collaboration in the fire mitigation space. The Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) has hired “Safety & Infrastructure Protection Teams” to provide additional personnel to assist their crews by helping trim trees near power lines, for instance.

Tell us more about the international community around first responders - they fly in from other states and countries to help the response. How formal or informal is this system and how close are we to this system breaking? What's needed to reinvigorate, reinvest, make it more sustainable?

It was quite amazing seeing pictures and videos of firefighting crews from Mexico and Canada on the ground in LA, wasn’t it? The international and interstate network of first responders is both highly coordinated and, at times, surprisingly informal. When disaster strikes—whether it’s a wildfire in California, an earthquake in Turkey, or a hurricane in the Caribbean—first responders from other states and countries often deploy to help. This happens through a mix of formal agreements, like FEMA’s Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC) and the UN’s International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (INSARAG), as well as more ad hoc efforts where individual NGOs deploy.

On paper, the system seems to work well. EMAC allows US states to send first responders across state lines, and international teams have trained together under INSARAG guidelines for decades. But in practice, the system runs on goodwill, overworked personnel, and increasingly tight budgets. Many departments can barely spare their own firefighters and EMTs, let alone send them elsewhere. And when disasters hit back-to-back—like hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria in 2017—it stretches the system thin.

A couple of things come to mind in terms of strengthening international disaster coordination. First, we should ensure that each country appropriately invests in its disaster capabilities. Similar to how one must first put an oxygen mask on oneself before putting one on another, we need to make sure we can take care of ourselves and avoid the resource challenges just mentioned. Secondly, let’s take care of the people who work to protect us. Many first responders and emergency managers are leaving the field due to burnout, low pay, and lack of mental health support. Firefighters and police officers are more likely to die by suicide than in the line of duty.

If we want to sustain this system, we need to take care of the people in it.

Lastly, a lot of international aid relies on goodwill rather than structured agreements. The European Union’s Civil Protection Mechanism has made major strides in pooling resources between countries, but globally, there’s no equivalent. A more formalised system—one that includes funding for rapid deployments and shared equipment—could reinvigorate the international disaster response system.

How do you see federal-level funding and workforce cuts, and calls for government efficiency impacting the emergency response space? And the sources of raw data e.g. NOAA that underpin those efforts? Should we be worried about federal, or get really worried when government efficiency efforts start to target state and local governments where there is arguably there's more inefficiency?

I fear that this question alone would require an hours-long interview, and I am extremely alarmed by what is currently unfolding. The recent cuts made by the government in the name of "efficiency" are compromising the safety and resilience of the United States. Take, for example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). NOAA is well-known for tasks such as publishing daily weather forecasts, issuing severe storm warnings, monitoring climate patterns, managing fisheries, restoring coastal areas, and supporting marine commerce. These functions are crucial for ensuring public safety and protecting our environment. Now, let’s also consider the following:

The National Weather Service, which is part of NOAA, issues tens of thousands of severe weather warnings each year, alerting millions of Americans of life-threatening conditions.

NOAA plays a critical role in providing weather observations and forecasts that address issues like turbulence, icing, and fog, which are essential for safe aviation operations.

Building codes are designed to withstand the forces of weather. To accurately determine these forces, we need to understand climatological patterns, a responsibility that falls to NOAA. Improvements in modern building codes over the past several decades are directly linked to the weather data and models developed from NOAA's information.

Private applications, such as The Weather Channel, rely on radar, satellite imagery, surface observations, and forecast models maintained by the NOAA network.

I fail to see how dismissing NOAA staff and cutting resources is making the government more efficient. These actions significantly increase our short- and long-term risks to natural and technological hazards at a federal, state, and local level. Like many agencies in the emergency management ecosystem, I would argue that NOAA saves the government more money than it costs to operate.

And finally, how should readers outside of the US take this all in, in terms of the US' ongoing capability to protect and defend against natural hazards and emergencies over the next four years?

If you’re watching all this unfold from outside the US, you might be wondering: how well is the US actually prepared to handle disasters in the coming years? The short answer? It’s a mixed bag. The US has some of the best-trained emergency managers and some of the most advanced disaster response systems in the world, but those systems are under serious strain, and some are at risk of being eliminated.

The good news is that the US has decades of experience mitigating, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from all kinds of disasters. There is incredible institutional knowledge across local, state, and federal agencies. Plus, technology, including satellite-based wildfire detection, flood modelling, and next-gen early warning systems, is advancing quickly.

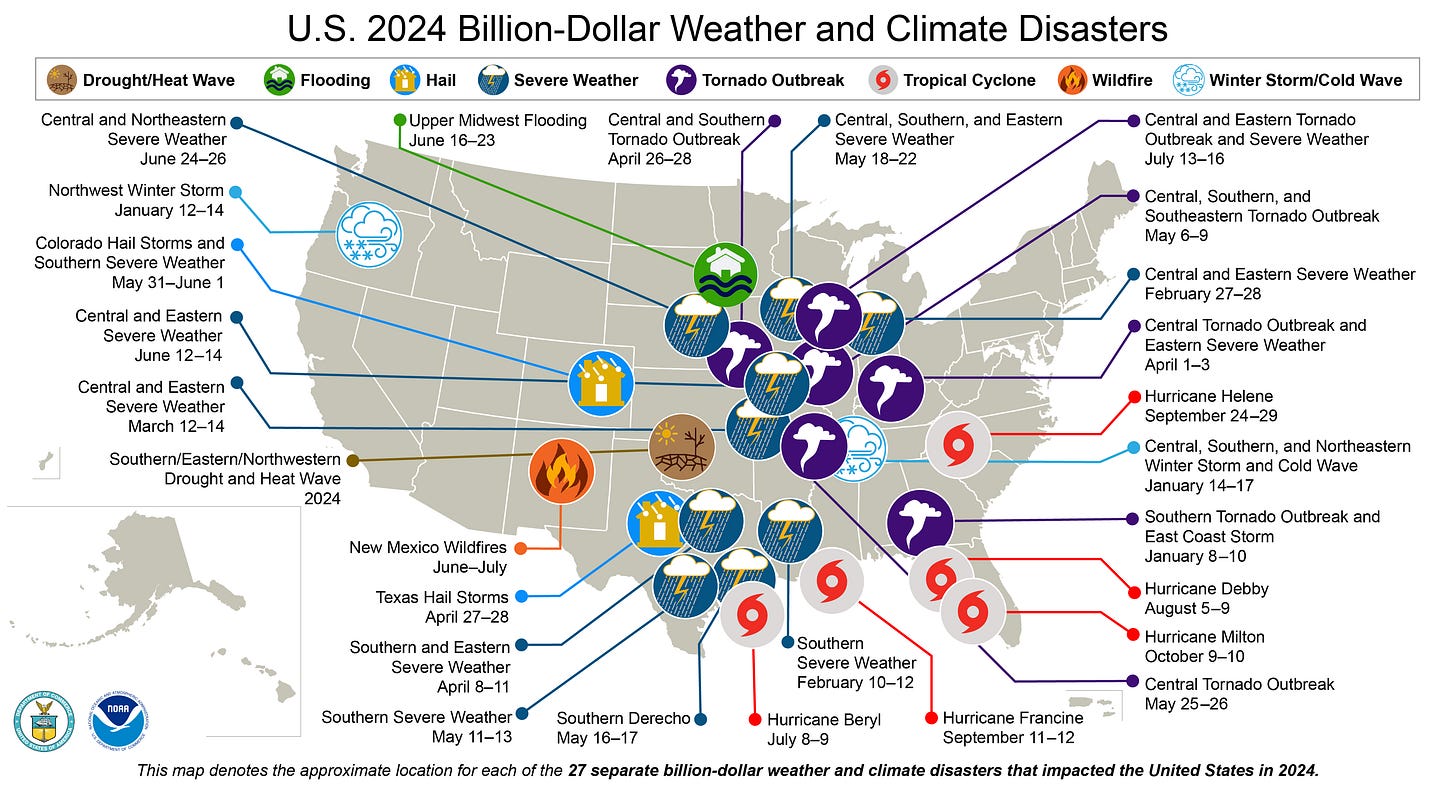

The not-so-good news is that we all know we are more reactive than proactive when it comes to building resilience. Funding shortages, aging infrastructure, and bureaucratic bottlenecks are making it harder to respond effectively. With climate change accelerating, the U.S. is expected to face more frequent billion-dollar disasters (NOAA recorded 27 in 2024 alone). That means the system will be tested even more. Meanwhile, adequate staffing and resource allocation remain issues across emergency management agencies, fire departments, and paramedic services across the country.

Most of all, I’m deeply worried about what’s happening to the US emergency management system—not just with FEMA but across the entire federal government. Managing disasters isn’t just about one agency; it’s a coordinated effort involving thousands of experts across the U.S. Forest Service, the Department of Energy, the CDC, and more. And right now, that system is being undermined in ways that will have lasting consequences.

We’re seeing mass dismissals of federal workers, the removal of decades of scientific data, and even restrictions on using terms like equity, climate crisis, and vulnerable populations. These aren’t just bureaucratic changes—they’re actively making it harder to plan for and respond to disasters. The people who always bear the brunt of disasters—the elderly, low-income communities, and people in high-risk areas—will be hit the hardest.

Let’s remember that disaster response isn’t just about reacting to crises—it’s about preparing for them. And that preparation depends on having the right people, the right information, and the ability to call things what they are. Without that, the entire system starts to break down.

And briefly, What caught my eye

A really troubling story from Zambia, where severe droughts leading to crop failures have pushed women in communities struggling to adapt towards fishing, where they are vulnerable to - and have been exploited - by men in the fisheries industry. A reminder what we discuss can have very direct consequences on the security and safety of most vulnerable.

US DoD and climate breakup: The Pentagon has predictably scrapped 91 climate-related studies and programmes as part of broader budget cuts, aiming to save $30 million annually. Also predictably, Democrats have criticised this decision, arguing it endangers national security by ignoring climate-related threats. What’s more interesting to see is if some DoD projects do survive, but under different guises or worked into other programmes e.g. base redevelopment and upgrades, advanced materials research, novel surveillance technologies etc.

What happens to climate protests in the new Trump era? Well, they did show up vocally at a major energy conference in Houston. Something tells me their job got just that much harder - the push for domestic resilience creates further headwinds for any meaningful dialogue, let alone progress, on a just transition.

And finally, I like a pandan chicken when get to visit Singapore and SE Asia. I’ve never wondered how it would taste in a military MRE. Well, to use a play on the old adage, even if you’ve never thought of it someone has, done it and reviewed it. Also recommend if you need some white noise:

See you again in a couple of weeks.